|

The 1892 Phillies

(image@fromdeeprightfield.com) |

|

Larry Bowa and Mike Schmidt celebrating

in the Phils' 1980 World Series Championship

parade on South Broad Street

(image@lancasteronline.com) |

We are now starting to reach the upper strata of the Phillies' greatest players. Here are numbers 11-20 in my ongoing list. For previous posts in this series, see

here,

here, and

here.

20. Elmer Flick (OF, 1898-1901)

|

| (image@sportsencyclopedia.com) |

Elmer Flick, a .313 career hitter and 1963 inductee (via the Veterans' Committee) of the Hall of Fame, is best known as a Cleveland Indian, for whom he played the last nine years of his career, leading the league in hitting in 1905, three consecutive years in triples (1905-07), and twice in stolen bases (1904, 1906). But he played his first 4 seasons for the Phillies at the Baker Bowl on Broad and Huntingdon in North Philly, where he replaced future Hall-of-Famer Sam Thompson in the cozy confines of the Bowl's right field. During those 4 seasons he hit a cumulative .338, scored 400 runs, drove in 377 (one more than he would do in his 9 seasons in Cleveland), and stole 119 bases. His best season was 1900, when he led the National League with 110 RBIs, and almost won the Triple Crown: he finished second to Honus Wagner with a .367 batting average and second to the Boston Beaneaters' (later the Braves) Herman Long with 11 home runs. He also scored 106 runs (tied for 6th), hit 32 doubles (tied for 3rd), 16 triples (tied for 4th), stole 35 bases (9th), had 200 hits (4th), and a slugging percentage of .545 (2nd). After another fine season in 1901 (.333, 112 runs, 88 RBI), Flick jumped to the Philadelphia Athletics in the upstart American League in 1902. When the Peensylvania Supreme Court ruled that he could not play for Connie Mack's A's, he was placed on the Indians, where he would play for the rest of his career.

19. Sherry Magee (LF, 1904-14)

|

Library of Congress Image of Magee in 1911

(image@notinhalloffame.com) |

The hotheaded Sherry Magee is one of the great, unappreciated players in Major League history. In his 11 years for the Phils, Magee scored 898 runs (leading the league with 110 in 1910), had 1647 hits (leading the league with 171 in 1914), 337 doubles (leading the league with 39 in '14), 127 triples, 75 home runs (hitting 15 in both '11 and '15, good enough for 3rd in the NL both seasons), drove in 886 runs (leading the league with 85 in '07, 123 in '10, and 103 in '14), stole 387 bases, batted .299 (leading the league at .331 in '10), and slugged .447 (leading the league at .509 in '10 and .507 in '14). During his career in Philly, Magee had a 142 OPS+ and a cumulative WAR of 47.9, leading the NL in offensive WAR in both '11 and '14. After the 1914 season, the 6th place Phils traded Magee to the pennant-winning Braves. Unfortunately for Magee, the Phils won their first pennant in 1915 by 7 games over the Braves. A good case can be made that Magee has been unfairly overlooked for the Hall of Fame. On merit he is a marginal case. But what has probably sealed the Irishman's fate as an outsider was his assault of umpire Bill Finneran after he struck out in a game in July of 1911. For his fit of rage, Magee was fined $200 (!) and suspended for the remainder of the season.

18. Scott Rolen (3B, 1996-2002)

|

| (image@metsmerizedonline.com) |

Scott Rolen is one of my least-favorite Phillies stars of the last 50 years. He is also, in my opinion, the greatest-fielding third baseman I have ever seen not named Brooks Robinson, which one would not guess when looking at his hulking (6'4", 245 lbs.) frame for the first time. He was also a pretty fair slugger who hit 316 home runs, drove in 1287 runs, and batted .281 in his career despite debilitating back problems that likely cost him a plaque in Cooperstown. For the Phils he started off with a bang, winning the NL Rookie of the Year award in 1997 on the merits of his 21 homers, 92 RBIs, and .283 batting average. In '98, he avoided the dreaded sophomore slump by having his best year as a Phillie, smashing 31 homers, driving in 110 runs, batting .290, and winning his first Gold Glove. During the next three seasons he continued his exemplary play despite missing 95 games due to injuries, never failing to hit at least 25 home runs, batting .298 in 2000, and driving in 107 runs in 2001. But the front office's niggardly ways and apparent failure to prioritize winning rubbed Rolen the wrong way, and he became more sullen by the year, ultimately forcing the team to deal him at the next season's trading deadline to St. Louis, where he would have his best season (2004) and play on the 2006 Cardinals' World Series championship team. Rolen was right about the Phillies' front office stinginess. But he handled it poorly, both with the media and a lack of appreciation for the team's fans. And both are a shame.

17. Jim Bunning (SP, 1964-67, 70-71)

|

Bunning's classic 1964 Topps card

(from the author's personal collection) |

|

| (image@pittsburghsportsreport.com) |

When the Phillies traded the power-hitting Don Demeter to Detroit before the 1964 season for Jim Bunning, the 32 year old Kentuckian was already a star, winning 118 games and making 5 All Star teams while with the Tigers. What they didn't know is that the 6'3" Bunning's best years were still ahead. Indeed, his first 4 years in Philly propelled him to his election to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans' Committee in 1996. From 1964-67 Bunning had a record of 74-46, pitched 1191.2 innings (leading the pitching-stacked NL in '67 with 302.1), and struck out 992 batters (leading the league with 253 in '67). He won 19 games three straight seasons ('64-'66), led the NL in shutouts in '66 and '67, and had steadily-declining ERAs of 2.63, 2.60, 2.41 (ERA+ of 150), and 2.29 (ERA+ of 149). After the '67 season the Phils, deeming the 36 year old Bunning a safe bet to decline, dealt him to the Pirates for Woodie Fryman and Don Money. For once the team made the right decision. In the "Year of the Pitcher" (1968), Bunning slipped to 4-14 with a 3.88 ERA (his 75 ERA+ that year shows how dreadful that seemingly decent ERA was in that era). In 1970 the Phils reacquired Bunning, though he struggled mightily for two years on dreadful teams, going a combined 15-27. Nonetheless, his second tour of duty in Philly allowed him to become the first pitcher since the venerable Cy Young to win 100+ games in both the National and American Leagues. In his six years for the Phillies, Bunning went 89-73 with a 2.93 ERA (122 ERA+). For his career he won 224 games, success he later parlayed into a long career in the US Senate.

16. Cy Williams (CF, 1918-30)

|

| (image@lonecadaver.com) |

.jpg) |

| (image@phoulballz.com) |

The tall (6'2"), lanky (180 lbs.) Cy Williams was the National League's premier power hitter in the 1920s, three times leading the Senior Circuit in home runs (15 in '20, 41 in '23, and 30 in '27). His dead-pull hitting style perfectly fit the cozy dimensions of the Baker Bowl (280' down the right field line and only 300 to the right-center power alley; the "saving grace," if one is to be sought, may have been the 60' high tin wall emblazoned with a huge Lifebuoy ad ["The Phillies use Lifebuoy"]), which somewhat mitigated the results of the shift defenses pioneered against him. In his eight prime seasons for the Phils ('20-'27), Williams hit better than .300 six times (ironically, the two years he didn't were his two best home run seasons, '23 and '27). For his Phillies career (5077 at bats over 13 seasons), Williams hit 217 home runs, drove in 795 runs, and batted .308, with a slugging percentage of .500 and an OPS+ of 131.

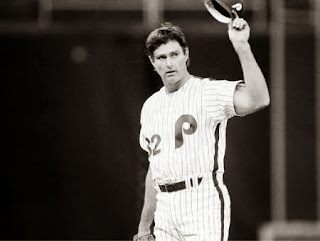

15. Curt Schilling (SP, 1992-2000)

|

| (image@philly.com) |

|

| (image@bleacherreport.com) |

Curt Schilling, in my opinion, should be a sure-fire Hall of Famer, despite the outrageously low 39% of the vote he got this year in his first year of eligibility [the fact that the decidedly inferior Jack Morris received 68% of the vote gets my dander up and demonstrates the incompetence of many of the writers who do the voting]. Unfortunately, he is best known for his remarkable 2001-02 seasons with the Arizona Diamondbacks and 2004 season with the Boston Red Sox, in each of which he won more than 20 games, finished 2nd in his league's Cy Young voting, and distinguished himself with memorable postseason performances. But that is a shame, for he won 101 of his career 216 victories (against only 147 losses) while playing for the Phillies. In his first year for the Phils (1992) he came out of nowhere to post a 14-11 record with a 2.35 ERA (150 ERA+) and an NL-leading 0.990 WHIP. The next year he went 16-7 for the pennant-winning Phils and pitched admirably in both postseason series, memorably shutting out the Toronto Blue Jays in game 5 of the World Series, which turned out to be all for naught because of Mitch Williams's bookending meltdowns in games 4 and 6. Schilling came into his own in 1997-99, in each of which he was named to the NL All Star team, winning 47 games and posted ERA+ marks of 134, 143, and 134. In '98 he led the NL with 15 complete games and 268.2 innings pitched. Even more significantly, he proved himself to be the league's premier power pitcher, striking out a league-leading 319 batters in '97 and 300 in '98. However, Schilling, like Scott Rolen, became increasingly frustrated by the team's apparent lack of commitment to winning, and so forced the trade to the Diamondbacks during the 2000 season. The rest is history. Schilling still ranks 6th in Phillies history with 101 wins, 7th in WHIP (1.120), 4th in strikeouts (1554), and 4th in WAR for pitchers (36.8).

14. Chuck Klein (RF, 1928-33, 36-39, 40-44)

|

| (image@dickallenhofblogspot.com) |

|

Philly's Two Great Sluggers of the early 1930s:

Klein (l) with the A's Jimmie Foxx

(image@theworldsbestever.com) |

Chuck Klein was, if you will, Philadelphia's Ryan Howard 80 years before the Big Piece: a powerful left-handed slugger who terrorized the NL for 5 or so years while playing in a very homer-friendly ballpark, but who, for various reasons, slipped from peak performance at a fairly early age. But Klein was better, arguably far better than Howard. In his first 5 full seasons in North Philly Klein led the NL in runs scored 3 times, hits twice, doubles twice, home runs 4 times, RBIs twice, stolen bases (!) once, batting once, total bases 4 times, and slugging twice. The line from his 1930 season is simply staggering: 250 hits, 158 runs (led league), 59 doubles (led league), 40 homers, 170 RBIs, .386 batting average, .687 slugging percentage. He was great that year, as his 6.9 offensive WAR (3rd in NL) and 159 OPS+ attest. But that was the year in which Bill Terry hit .401 for the

Giants, fireplug Hack Wilson of the Cubs hit 56 homers and drove in 191 runs, and the league batting average was .303. His best season was to come three years later, when he won the Triple Crown—Jimmie Foxx of the Philadelphia A's won the AL's Triple Crown that season, the only time the rare feat was accomplished in both leagues the same season—with 28 homers, 120 RBIs, and a .368 batting average (along with a league-leading 7.8 offensive WAR an 176 OPS+). Ironically, having won the NL MVP in 1932, he lost out to Giant hurler Carl Hubbell in '33. In classic Philadelphia fashion, however, Klein was traded after the season to the Cubs for Mark Koenig, Ted Kleinhans, and Harvey Henrick (have never heard of them? Don't feel bad. No one else has either). The only saving grace, if there was one, is that Klein's production, while still good, dropped significantly in Chicago. After a little more than two years in the Windy City, he was traded back to the Phillies, but apart from one memorable game, he was not the Chuck Klein of old. That one game occurred on 10 July 1936 at Pittsburgh's Forbes Field. Klein that day hit 4 home runs, the last one a shot in the top of the 10th inning to carry the Phils to a 9-6 victory over the Bucs. He is one of only 16 players in the history of the game to accomplish this feat. Nonetheless, for the season he hit only 20 homers and batted .309. The next season he raised his average to .325, but he only hit 15 homers and his slugging slipped to .495, never to return again to the .500 mark. Evaluating Klein is somewhat difficult because of where he played. Perhaps no one in baseball history was more helped by the park in which he played (apart from Mel Ott?). The Baker Bowl, with its 280' right field fence and 300' right-center power alley, was a generator of doubles and cheap homers, and Klein obliged. In each of his prime seasons, Klein's home records far surpassed what he did on the road, but his last two are particularly striking. In '32, he hit 29 homers and batted .423 at home, 9 homers and .266 on the road. In '33, he hit 20 homers and batted .467 (!) at home, 8 homers and .280 away. What would he have done had he played his career a few blocks away at Shibe Park? One will never know. As it was, he hit 243 of his 300 lifetime home runs for the Phillies, batting .326 and slugging .553. Klein was finally inducted into the Hall of Fame after being voted in by the Veterans' Committee in 1980.

13. Nap Lajoie (2B, 1B, 1896-1900)

|

| (image@bleacherreport.com) |

.gif) |

| (image@philadelphiatale.wordpress.com) |

Napoleon Lajoie is best known as a Cleveland Indian because of the 13 seasons he played there (1902-14). But his first 6 seasons were played in Philadelphia, the first 5 for the Phillies. In his first full season (1897) he drove in 127 runs, batted .361, and led the league in slugging with a .569 mark. In '98 he slipped a little (.324, .461), but still led the league with 43 doubles and 127 RBIs. After two more great seasons in which he batted .378 and .337. Lajoie defected to Connie Mack's A's in the fledgling American League, where he promptly had what is arguably his greatest season in 1901, winning the Triple Crown with 14 homers, 125 RBIs, and a .426 batting average (he also led the league in runs [145], hits [232], doubles [48], slugging [.643], and OPS+ [198]). The next year, following a ruling by the Pa. Supreme Court that Lajoie's defection to the AL violated the NL's reserve clause, he was sent to Cleveland, where he would lead the Al in batting three more times. For his career Lajoie amassed 3243 hits and batted .338, but for the Phillies he hit .345. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1937, in only the second year of balloting, along with Tris Speaker and Cy Young.

12. Sam Thompson (RF, 1889-98)

|

| (image@atlantabraves.mlb.com) |

|

| (image@baseball-fever.com) |

Big Sam (6'2", 207 lbs.) was the Phillies' earliest batting star. When the team bought his services from the Detroit Wolverines prior to the 1889 season, he had already established himself as one of the game's top players, having led the NL in hits (203), triples (23), RBIs (166), batting (.372), total bases (308), and slugging (.565) in 1887. When he came to Philly he picked up where he left off, becoming the first player to hit 20 homers in a season, scoring 103 runs, driving in 111, and batting .296 in '89. Over the next 7 seasons, Thompson drove in at least 100 runs in 6 of them. He reached his peak in the 3 years beginning in 1893, when he was already 33 years of age. In '93 he led the league in hits (222) and doubles (37), hit 11 homers, drove in 126 runs, batted .370, and slugged .530, with an OPS+ of 151. In '94 he hit 13 homers, drove in a league-leading 147 runs, batted .415, slugged a league-leading .696, with an OPS+ of 182, also tops in the league. In '95 he led the NL with 18 home runs, 165 RBIs, and a .654 slugging percentage, while batting .392 with an OPS+ of 177. For his Phillies career, Thompson batted .334, scored 930 runs, drove in 963 runs, and slugged .509, with an OPS+ of 144. With 127 career homers for the Wolverines and Phillies, Thompson hit more than any other player before the beginning of the 20th century. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1974 by the Veterans' Committee.

11. Gavvy Cravath (RF, 1912-20)

|

| (image@baseballrealitytour.com) |

|

| (image@baseball-fever.com) |

Gavvy Cravath was the greatest slugger of baseball's dead ball era. His 119 career home runs were more than anyone else in the first two decades of the 20th century. And he did it despite not becoming a regular player until he was 31 years old in 1912, when the Phillies brought him up from Minneapolis and promptly placed him in right field. Despite hitting only 2 home runs in 333 at bats for 3 AL teams in 1908-09, he immediately showed unexpected pop in his bat, hitting 11 home runs and slugging .470 his first year in Philly. Over the next 7 years he paced the NL in homers 6 times, RBIs twice, OBP twice, total bases twice, slugging twice, and OPS+ 3 times. Cravath had his best season in 1913, when he led the NL in hits (179), home runs (19), RBIs (128), total bases (298), slugging (.568), and OPS+ (172), while batting a career-high .341. In the Phils' 1915 pennant-winning season, he was almost as good, leading the league in runs (89), homers (24), RBIs (115), walks (86), OBP (.393), total bases (266), slugging (.510), and OPS+ (170), while hitting .285. In his nine years in Philadelphia, Cravath hit 117 home runs, drove in 676 runs, batted .291, slugged .489, and amassed a staggering cumulative OPS+ of 152. One can only imagine the numbers he would have put up had he played a decade or two later.

.jpg)

.gif)